General Introduction to Island Forest History and Ecology

The Acadian Forest

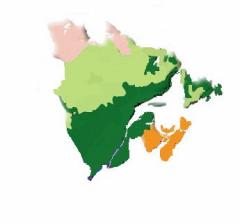

Prince Edward Island is part of Canada's Acadian Forest region. This forest region (orange) covers all of PEI and Nova Scotia and most of New Brunswick. Ecologically, it is very similar to the Great Lakes-St Lawrence Forest Region of central Canada and the much larger Transition Forest Region of eastern North America. The name "Acadian Forest" was derived from the general region settled by the Acadians in the 17th and 18th Centuries.

Prince Edward Island is part of Canada's Acadian Forest region. This forest region (orange) covers all of PEI and Nova Scotia and most of New Brunswick. Ecologically, it is very similar to the Great Lakes-St Lawrence Forest Region of central Canada and the much larger Transition Forest Region of eastern North America. The name "Acadian Forest" was derived from the general region settled by the Acadians in the 17th and 18th Centuries.

On rich, well-drained soils and on upland sites, Island forests tend to be dominated by Northern Hardwood Forest species such as American Beech, Yellow Birch, Sugar Maple, White Pine, Eastern Hemlock, Red Oak and White Ash. On poorly drained sites, poor soils, exposed coastal areas or areas recovering from significant disturbances such as fire, insects, land clearances or harvest activities, the forest will usually be dominated by Boreal Forest species such as White Spruce, Black Spruce, Eastern Larch, Poplar, or White Birch. Balsam Fir and Red Maple tend to occur in all Island stand types. Other tree species such as Jack Pine, Red Pine, Eastern White Cedar, Ironwood and Black Ash occur in specific areas or have limited ranges on P.E.I. Rural populations of American Elm have been largely extirpated by Dutch Elm Disease.

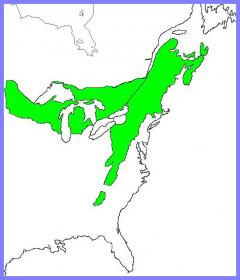

The Transition Forest (green area) marks the region where Boreal Forest species of the north overlap with more southerly species from the Deciduous (Northern Hardwood) Forest Region. This forest stretches from the Maritimes west across the Great Lakes to the borders of Manitoba and Wisconsin and south through New England and along the Appalachians into northern Georgia.

In the original, pre-European forest, most of the Island's Acadian Forest was composed of mixed species stands with a high percentage of shade tolerant species. Stand structure was multi-aged with distinct canopy, understory and ground vegetation layers. This forest was self sustaining with young seedlings growing in the deep forest shade. When openings occurred as older trees died or blew over, the young trees would grow quickly to reach the canopy level and start the cycle again. Large dead trees in various states of decay covered much of the ground, recycling nutrients, creating habitats for many forest plants, animals and insects and helping to build deep rich soils.

Many Acadian Forest tree species can reach 200 years of age or older. Sugar maple and white pine are capable of living for as long as 400 years while eastern white cedar and eastern hemlock have been known to reach nearly 1,000 years of age in some parts of their North American range. These old giants produced large volumes of edible seeds for birds  and mammals and supported many different species of lichens and mosses on their bark and branches. Many developed large hollows or “cavities” in the trunk that could be used as denning and nesting sites for larger mammals and birds of prey. Taller trees also offered excellent vantage points for predators, while their large branches provided vertical structure within the forest.

and mammals and supported many different species of lichens and mosses on their bark and branches. Many developed large hollows or “cavities” in the trunk that could be used as denning and nesting sites for larger mammals and birds of prey. Taller trees also offered excellent vantage points for predators, while their large branches provided vertical structure within the forest.

Boreal species such as spruce, larch and poplar tend to be shorter lived. In order to renew themselves, they often depend upon major disturbances that create large openings in the forest with full sunlight. For example, the spruce budworm and the eastern tent caterpillar are native forest insects that periodically experience massive outbreaks in mature to overmature stands. Outbreaks can destroy thousands of hectares of forest, creating large areas of dead trees that present a significant forest fire risk. Because they are adapted to disturbance conditions, Boreal Forest tree species will quickly renew these sites, creating an even-aged forest and beginning the process all over again.

Shade tolerant species such as sugar maple, white pine and yellow birch prefer a different approach to renewal. Rather than the sudden and large scale disturbances common to spruce and fir, mortality in these species is usually more gradual. In mixed stands, trees tend to decline and die as individuals or in small groups. This means that most of the forest floor remains in deep, cool shade. Seed from adjacent trees will germinate quickly in these shaded areas and soon young, shade tolerant tree species will begin to reach up toward the gaps in the canopy.

Eventually, even the mightiest tree will fall, but its role in the forest is far from over. Large dead trees can take decades or even centuries to decompose, contributing to many different ecological processes in Island forests. These processes build forest soils, create room for new trees and shrubs to grow, and provide food, shelter and habitat for a wide range of wildlife.

The overlapping of the Boreal and Northern Hardwood Forest regions creates a rich biodiversity, as many plant and animal species are near the northern or southern limits of their natural ranges. For instance, the white birch (B papyrifera) ranges from north of the Arctic Circle, south into parts of Pennsylvania, so on a continental basis the Island is near the southern part of its range. Its close cousin, the yellow birch (B alleghaniensis), ranges from South Carolina north to the Gaspe' and parts of Newfoundland, so P.E.I. is at the northern end of its range. As this picture illustrates, the Acadian Forest region provides habitat for both species and they are often found growing side by side.

limits of their natural ranges. For instance, the white birch (B papyrifera) ranges from north of the Arctic Circle, south into parts of Pennsylvania, so on a continental basis the Island is near the southern part of its range. Its close cousin, the yellow birch (B alleghaniensis), ranges from South Carolina north to the Gaspe' and parts of Newfoundland, so P.E.I. is at the northern end of its range. As this picture illustrates, the Acadian Forest region provides habitat for both species and they are often found growing side by side.

Forest history: the last ice age to 1900

At the end of the last Ice Age some 10,000 years ago, Prince Edward Island was covered by ice that was a kilometre or more thick. Over the next several thousand years, the ice retreated and the landscape began to transition from ice cover to Tundra, then to Taiga, and eventually to a Boreal Forest type of ecosystem. Over the next few thousand years, the climate warmed and richer soils developed enabling more southerly species such as maple, pine, ash and oak to begin colonizing the Island's landscape and mix with the spruce, larch, birch and poplar already growing here. Eventually, the ocean filled the Northumberland Strait, cutting the Island forest off from further tree migration.

PEI forest cover - 1700

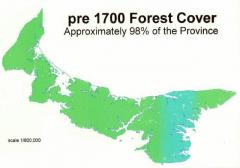

At the onset of European settlement in the early 1700s, forests covered some 98 percent of the Island's surface with the remainder divided among ponds, wetlands and sand dunes. Often the hills and valleys were covered with huge old maple, birch, beech and oak trees as well as large white pine, spruce and hemlock. Indeed, many early visitors to our Island wrote descriptions of trees as much as 3m across at the base and more than 30m tall! They also noted the difficulties large fallen trees presented when traveling from one community to another and commented on the effort required to fell and remove these huge trees to create farms, settlements and roads.

Beginning with the first significant European settlements in the 1720s - and continuing well into the 1800s - much of P.E.I.'s forest was cleared for habitation and farmland. Even areas that were not cleared were heavily altered through the use of fire, hygrading (taking the best quality trees and leaving the rest) and constant harvest pressure on the remaining forest for building materials and fuelwood.

Beginning with the first significant European settlements in the 1720s - and continuing well into the 1800s - much of P.E.I.'s forest was cleared for habitation and farmland. Even areas that were not cleared were heavily altered through the use of fire, hygrading (taking the best quality trees and leaving the rest) and constant harvest pressure on the remaining forest for building materials and fuelwood.

Several animal species were also lost during this period. The passenger pigeon is PEI's only extinct forest animal but other species such as the black bear, moose and woodland caribou were extirpated from Island forests due to habitat loss and hunting pressures to reduce crop and livestock losses.

New creatures such as the striped skunk, racoons and coyotes and plants such as Glossy Buckthorn and Japanese Knotweed were also added to the Island's forest ecosystem. Diseases such as Dutch Elm Disease (DED) virtually eliminated wild elm stands on P.E.I. While not as lethal as DED, Beech Canker Disease also had a profound effect on the quantity and quality of Island beech trees. Fortunately, this species seems to be recovering but the process is still ongoing.

1900 to today

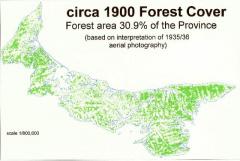

By 1900, only about 30 per cent of the Island remained under forest cover. Large scale clearances for agriculture and other human uses, combined with the constant harvest pressure on the remaining resource led to significant changes in the mixture of tree species and a serious decline in the overall health and quality of Island forests.

pressure on the remaining resource led to significant changes in the mixture of tree species and a serious decline in the overall health and quality of Island forests.

Through much of the early 20th Century, people began to leave Prince Edward Island for opportunities in other places. Often they simply abandoned their farm land and over time, the forest began to reclaim the old fields. By 1990, forests once again covered about 48 percent of the Island's surface area, most of it east of Charlottetown and West of Summerside. However, this "new" forest was very different from the Acadian Forest of earlier times.

The forest has been heavily fragmented and most properties contain dozens of small stands composed of young, small diameter trees. Mixed stands of sugar maple, yellow birch, beech and white pine have often been replaced with stands composed of red maple, poplar, white spruce, larch and balsam fir. Abandoned old fields reverted to single species, white spruce. Unlike other Acadian Forest species, white spruce was able to establish itself on heavily grassed sites and compete for growing space and light. While white spruce produced many valuable products, the way these stands established themselves often led to problems with early mortality and low quality.

By the end of the 20th Century, the Island's forest area was once again in decline. The 2000 Forest Inventory found that the total forested area had fallen from 48 percent in 1990 to 45 percent 2000, largely due to conversions to agriculture, blueberries and other developments in rural areas. The 2010 State of the Forest Report found that the decline in the Island's forest area continued and today, forest cover some 43.9 percent of the province.

The future:

While the Island's high percentage of private forest lands makes it difficult to achieve common goals, surveys indicate that Island land owners care deeply for their woodlands and use them for many different purposes. The primary issues facing the Island forests continue to be poor harvest practices and conversion of forests to agricultural, commercial and residential developments.

Over the last 10,000 years, the Island's climate has undergone several periods of warming and cooling due to a range of natural influences and processes. However, in recent years concern has grown over the increasing role human activities have on the world's climate. With this in mind, studies and research are being conducted into the potential effects of climate change on Island forests. Most climate change models predict significant challenges for many tree species over the coming century. This will require land owners, government and others to begin planning for the next phase of development in the Island's Acadian Forest.

While we may not be able to restore all of PEI's historical wood lands, most people believe that we should strive to improve the health of our remnant forests by enhancing - not degrading - natural ecological processes and functions in Island forests. The Forest Enhancement Program offers a wide range of services to private forest owners who want to restore forest health on their lands.